Yars’ Revenge to ET: Howard Scott Warshaw’s Atari Journey

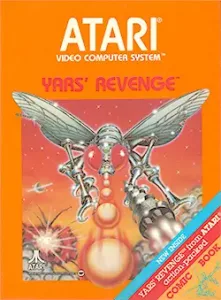

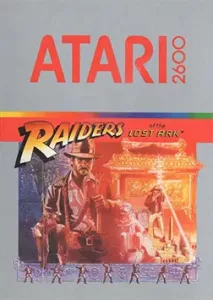

In this episode of OH!CAST, we explore the remarkable career of Howard Scott Warshaw, the Atari designer whose work defined both the creative heights and infamous challenges of the early video game industry. From the groundbreaking originality of Yars’ Revenge to the ambitious adaptation of Raiders of the Lost Ark, and finally to the rushed development of E.T. the Extra‑Terrestrial, Warshaw’s story is one of innovation, risk, and resilience. The keyphrase Yars’ Revenge to ET captures the arc of his journey and the cultural impact of his games.

The story of Howard Scott Warshaw is often summarized in one phrase: Yars’ Revenge to ET. This OH!CAST episode explores how one designer’s career at Atari captured both the creative triumphs and the infamous challenges of the early video game industry. From the groundbreaking originality of Yars’ Revenge to the ambitious adaptation of Raiders of the Lost Ark, and finally to the rushed development of E.T. the Extra‑Terrestrial, Warshaw’s journey demonstrates how innovation thrives under constraints.

From Star Castle to Yars’ Revenge

Warshaw’s first assignment at Atari was to convert the arcade game Star Castle to the Atari 2600. Recognizing that the hardware could not handle the vector‑based design, he boldly rejected the project and pitched a new concept. That decision led to Yars’ Revenge, a title that broke new ground in graphics, sound, and gameplay. Unlike the endless stream of Space Invaders clones, Yars’ Revenge offered unique mechanics and striking visuals that pushed the limits of the 2600. It quickly became one of the console’s best‑selling and most beloved games, establishing Warshaw as a designer who could transform constraints into creativity. The phrase Yars’ Revenge to ET begins here, with a bold refusal and a breakthrough success.

Raiders of the Lost Ark: Adventure Redefined

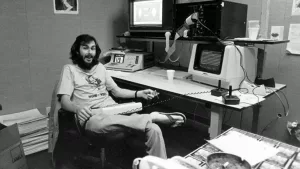

Following the success of Yars’ Revenge, Warshaw was chosen to design Raiders of the Lost Ark, the first licensed movie‑to‑game adaptation in history. Spielberg himself interviewed Warshaw before approving him for the project. The result was a complex adventure game that used two controllers simultaneously, introduced inventory management, and offered puzzles and exploration far beyond the typical action titles of the era. While challenging without a manual, Raiders remains a landmark in gaming history, remembered for its ambition and depth. This middle chapter in the Yars’ Revenge to ET arc shows how Warshaw expanded the boundaries of what adventure gameplay could be.

ambition and depth. This middle chapter in the Yars’ Revenge to ET arc shows how Warshaw expanded the boundaries of what adventure gameplay could be.

E.T.: The Five‑Week Sprint

Warshaw’s most famous project, E.T. the Extra‑Terrestrial, was developed under extraordinary pressure. Given only five weeks to design, program, and deliver a game based on Spielberg’s blockbuster film, Warshaw produced a title with exploration, item collection, and multiple win conditions. While the infamous pits frustrated many players, others found charm in its ambition. The episode examines how E.T. became a scapegoat for Atari’s broader collapse, while also highlighting Warshaw’s achievement in delivering a complete licensed game under impossible constraints. The phrase Yars’ Revenge to ET captures this dramatic shift from creative freedom to crushing deadlines.

Innovation Under Constraints

A recurring theme in Warshaw’s career is innovation under constraints. Whether pushing the Atari 2600’s primitive hardware to create dazzling visuals, redefining adventure gameplay with dual controllers, or racing against the clock to deliver E.T., his work demonstrates how creativity thrives when boundaries are tight. The episode also explores the cultural impact of his games, including how Yars’ Revenge unexpectedly resonated with adult women, challenging stereotypes about who plays video games. The journey from Yars’ Revenge to ET is not just about games; it is about how pressure can fuel breakthroughs.

Beyond Atari

Warshaw’s journey did not end with Atari. He later became a therapist, applying his systems‑analysis mindset to human psychology. His reflections on interdepartmental conflicts at Atari—between engineering and marketing—remain relevant to software development today. His book Once Upon Atari provides further insight into these experiences, and OH!CAST highlights how his career continues to inspire discussions about creativity, pressure, and resilience in the tech world. The phrase Yars’ Revenge to ET has become shorthand for a career that shaped gaming history and continues to resonate decades later.

Why Listen

This OH!CAST episode is more than a nostalgic trip. It is a study in how innovation, risk, and human determination shape creative industries. For retro gaming fans, Yars’ Revenge to ET offers insider stories about Atari’s most famous titles. For creators and developers, it is a reminder that constraints can fuel breakthroughs. And for anyone curious about the intersection of pop culture and technology, Warshaw’s journey is a compelling narrative of triumphs, challenges, and lasting influence.

Chapters

00:00 Introduction to Howard Scott Warshaw

02:11 The Making of Yars’ Revenge

12:01 Yars’ Revenge and Its Unique Appeal

20:56 The Challenge of Raiders of the Lost Ark

30:38 The Controversy of E.T.

31:44 The Mechanics of Game Design

34:17 Best and Worst Games on the 2600

36:34 The Rise of Activision and Imagic

37:58 Ironies of ET and Industry Pressure

42:11 The Urban Legend of Buried Games

46:21 Emotional Reactions to Game Legacy

47:49 The Homebrew Community and New Developments

50:14 Quickfire Questions and Final Thoughts

Full Transcript

Speaker 2 (00:01.454) you Speaker 2 (00:07.382) Jai Rameshwari, God my edge, Devokha Speaker 2 (00:14.19) Right, good evening everyone and welcome to OCAST, your Ireland gateway to all things geek. I'm your host tonight, Conor MacDonald and in a rare reappearance, Hedoward, you're joining us tonight. Yeah, thanks so much. I've been pulled out. tried to get out, but they pulled me back in again. I'm absolutely so excited. I'm trying not to fanboy all over the place. It can be, can be an unfortunate. But yeah, I'm so excited that we've got legendary game designer Howard Scott Walshaw with us here today. Thank you so much for joining us. Thank you for having me. am truly looking forward to being had. For those who don't know, Howard worked for Atari in the 1980s when the VCS or the 2600 system was dominating the gaming scene. And Howard, in the space of, I think, two years, is it? Or was it all three games were released in one year? Is that right, Howard? They were developed over the course of about 18 to 20 months and they were mostly released in 82 because yours was the most tested game in the history of Atari games, which was interesting. So that delayed the release. That's a whole nother story. I got plenty of stories for you. Speaker 2 (01:38.796) We look forward to hearing them. So Howard has been responsible for three of Atari's, the 2600's most famous games, Yars Revenge, Raiders of the Lost Ark, which I believe is the first video game adaptation of an Indiana Jones, of Indiana Jones, but it's also the first of any movie. first video game adaptation of any movie and also then ET, which we'll come to in a bit. Yeah, that was another movie. I'd like to start with Yars Revenge. I do. I want say is I love Yars Revenge. Thank you for Yars Revenge. It is such a Speaker 1 (02:14.616) Why not? Speaker 1 (02:21.068) You're welcome. Thank you. I never get tired of hearing that strangely enough. It is such a unique game. For those who aren't totally familiar with the Atari VCS or the 2600, it was very much a kind of pew pew system. was, the graphics were very basic. There was pink bleeps and squeaks and all manner of sound effects, but it was not a sophisticated. At the time it was very sophisticated, but to modern gamers eyes, it looks like something that has crawled out of the primordial ooze. But Yars Revenge, I think, out of the hundreds of games that are on the system is definitely up there. It's one of the best, if not the best game on the system. And it's so unique. It's so unlike anything else on the 2600. Very much 2600 was just reams and reams of space invaders or phoenix kind of clones. And then Yars' Revenge is this far more complex fixed screen shooter, but it's It has such interesting mechanics. just tell us a bit about how Yars came about. Yars Revenge was my favorite. Interestingly, it was originally assigned as a coin up conversion of a game called Star Castle. But all the things that you mentioned, the dynamic visuals in it, the different sort of gameplay, the different screen orientation, there were a lot of things that were firsts in the industry in Yars Revenge, many of which went on to become standards. you mentioned, you well, what was I trying to do or where was I trying to go with it? Speaker 1 (04:00.182) I wasn't just trying to make a game. was trying to make a splash. This was my first opportunity to make a video game for Atari. And what was super important to me was to establish myself as a credible video game designer. This was a time when nobody knew what a video game designer was. It was a brand new thing to do, but I knew I needed to do it. I needed to do it there with the people who were doing it. And so my goal with that game was to do something that just grab people and pull them in. I wanted to use every aspect of the system. I wanted to innovate graphically. I think I innovated in the sound area as well because, you know, I came, most people came to Atari from a home computer hobbyist world. I came there from a math and economics background and a film buff. And so, When it came to producing entertainment on the system, I never really looked at it as a program as much as I looked at it as a very limited resource to provide a maximum entertainment impression. And if you think about Yars Revenge, I hope it's apparent from the things you see in Yars that that's where I was coming from. Because I developed some really interesting visuals, some stunning effects, and early on in the development, I had those things that looked really cool and people would come up to me and go, wow, that's really cool. I've never seen something like that before. What does it do? And I'd say, I don't know yet because I was, I was just putting these things on the screen that I, cause I wanted there to be something stunning first and then figure out what to do with it. And so step by step, it was this incremental process of finding something that's striking and then finding a way to enhance it and then finding a way to work it into the play. and then go back to the visuals and then back to the play. It was very much an incremental iterative process, but the goal was always very clear and that was to do something that was not just glittery, but something that was unusual, something that was unique, something people hadn't seen before and something that was compelling. And audio visual overload is what I was really going for. So that's, guess that's a fair introduction. By the way, I should say that if you're really interested in Speaker 1 (06:25.516) everything that Yars Revenge went through, which is a long story. It's all right here in this book, Once Upon Atari, How I Made History by Killing an Industry by me, Howard Scott Worshaw. And so this book is available throughout Scotland and the EU. And it's an ebook, it's a paperback, and it's also an audio book. And I read the audio books. I just wanted to take a moment to make sure people were clear about where they could find more information about Yars Revenge. and Raiders of the Lost Ark and the entire ET development and the trajectory of my life, both before and after Atari. That trajectory was totally not only altered, it was abused and refocused and then tumbled over. Atari is still impacting my life. It was one of the most amazing experiences a person could go through. Unbelievable place to be. And I'll see you. any of the sequels of Yars' Revenge with the exception of Game Boy. The Game Boy, which was done by Mike Micah, the first Game Boy Yars' Revenge, I did consult with Mike Micah and helped him develop some of the algorithms and things like that to operate Yars. But after that, I'm actually kind of proud to say I haven't had anything to do with any of the Yars' Revenge sequels because in my opinion, They're all just minor reworking is of the basic gameplay I did. have a decline for a Yars Revenge sequel that I'm looking, talking to Atari about dealing with now. That's an actual new gameplay, which to me, a sequel of Yars Revenge should have new gameplay, not just revamp the old gameplay, but that's just me. Speaker 2 (08:08.32) I was saying I wanted to come in there with like in preparation for this. I watched the documentary about the excavation of the landfill. again. Yeah. And in it, is this true? said like, well, how did you program the game? just said you read the code book and then you just worked from that when you were, when you made yards. Is that true? Well, I read the manual. Yeah, I read the manual. got the idea of the system. So the way it happened that was kind of interesting was first of all, you should know that Atari, how did I get to Atari? I was working at Hewlett Packard in a very staid classic, you know, software environment. And I was bored to death. I loved, loved, loved computers once I got into computers and all the passion I found in computers was lost for me at Hewlett Packard in a professional environment. So. And I started to act out. was a wild man at, at Hewlett Packard. I was kind of wild at Atari too, but at Hewlett Packard, was showed more. And, one day, one of the people there said, Hey, you know, I was telling my wife a Howard story the other day. She said, people do stuff like that all the time where I work. said, where's that? And she said, he's at Atari. His wife worked at Atari. This was the first time I'd ever heard of Atari as a place to work. I went there. I interviewed, I went through rounds and rounds and rounds of interviews. I thought it went really well. Everything seemed to be right on track. I had background and had expert level in the kinds of real time programming that they did, which was very unusual back then. And then they rejected me. Truly rejected me. I initially did not get into Atari, but I knew this was a place I had to be. And so I negotiated. kind of pushed my way in. And I negotiated myself a 20 % cut in pay and also a probation. put myself on probation for a while. I was just willing to do anything to get in to prove I could do it. said, let me in. I'll do anything. I'll do whatever you say. Just give me a chance. I know this is going to be a good match. And so they did give me a chance. And then after a few days, I read the manual. Then they gave me an assignment, star castle to convert that game. Speaker 1 (10:20.364) I started to look at and I realized that game was going to suck on the 2600. It was just, was a vector coin up game that was so maladapted for the 2600. It was just going to be horrible. And I couldn't afford to have my first game be horrible. I just wasn't going to do that. So on probation on like my fourth or fifth day working there, I go into my boss's office and I say, you know, the assignment you gave me, I'm not going to do it. I don't think it's a good idea. And, I didn't just say, don't want to do it. I had drawn up some designs and I had the concept of what became yards revenge. And I presented that. said, here's something that I think takes advantage of some of the game mechanics that work. gets rid of some of the game mechanics. I think that don't work. And I think it's much better adapted for this system. How about this? And to his credit, he said, okay, you know, give it a shot, go ahead and take a, they let me do it. They let me, and this was a license. to walk away from a license a few months later would have been unheard of at Atari, but he gave me the latitude. And so I started working and it wasn't yards revenge at that point. It was just this thing. Howard's working up because it wasn't star castle anymore. And it wasn't yards revenge yet. Cause how it becomes yards revenge is a whole nother fun story later on. That was my, my plan to out market marketing, but I just started making a game that I thought I would enjoy playing because I thought I like games. If I make a game I think is fun that I think is cool, it'll probably be okay. And that was my development ethos as I started the march through Yars Revenge. I hope that answers your question. does. You mentioned that Yars' Revenge was very heavily play-tested. But one thing I've heard is that in these play-tests, actually transpired it was really popular with women. This has continued to be the case. I'm thinking this is very similar to what we know about Pac-Man. Pac-Man was such a success because it appealed to both men and women. What is it about Yars' Revenge that appeals to women? Speaker 1 (12:30.2) Well, it's interesting you say that. mean, at the time, yeah, it was a big, big thing in the video game industry is that women were way underrepresented in the playership and they wanted to know how do we get women more involved with games and Pac-Man, everybody looked at Pac-Man and saw there's a game that really appeals to women. Women love acting. Women also like Centipede, which was the only coin up game that was designed by a woman. But Pac-Man was the standout game to appeal to women. then Yars. Star's Revenge, when it was time to try and release it, there was someone in the company who was against the game. I don't know why, I don't know what was going on in their head, but there was a person in Atari who had the ear of upper management who was against the game. And they kept saying there's problems with the game and they would test the game and they would test the game and it all came out fine. I was okay. So let's go, let's release the game because getting your first game released is a big big thing. There is a rite of passage at Atari that you need. I needed and I kept getting there and everyone was excited about the game and everybody thought it was a great game. Here we go. And then and then okay, so we're going to release the game. They go. wait, somebody says there's a problem with long-term playability. So now they want to do another test and it would would clobber the test. would do great in the test and then I go. Okay, here we go. Went through several focus groups. So finally they commissioned a play test. Now a play test is where they actually get a hundred people to come and play the game across all demographic groups. And they come and they play the game, the tart, they play the test game and they play it against a control game and they rate both games. So I'm thinking, okay, here we go. This is the big test. And the big question in a test like this is what's, what's the control game, right? What's the game you're going to test against? Because, you know, I believe if you're going to be the best, you need to beat the best. Right? mean, that's, you're going to be the best, you have to beat the best. That's what they say. However, if they would have picked a really second rate title to check it against, I would have been totally fine with that because I don't need a big challenge. I need to get my game out. And the word comes down and the game they're going to test against is missile command on the 2600, which I think is one of the best conversion. was the hottest game at the time. I think it was an, it was done by my friend, Rob Follett. Speaker 1 (14:50.702) who's an amazing designer and it's just a wonderful, really faithful delivery of that game. I screwed. And so, but I went to the play test and I'm all set. I have a degree in statistics. So I was ready to work the numbers on this test. And here comes the first sheet. And the first sheet is though they just trash yards entirely. They love missile command. They trashed yards revenge. I'm thinking, God, but That was the worst sheet for yards in the entire test. And it did the whole test when the smoke cleared yards revenge beat missile command in the play test. And then it was finally, okay, we're going to go. So I finally relieved. had a case of what you call releases interrupt us. I just couldn't quite get the game out. Then finally there it was. So the game went out, but in the, in the demographics, there's four demographic groups basically that they look at. And that's, you know, girls and boys and women and men, adult women and men. Those are the four groups. And all the groups liked it really well, but the group, the one group that liked it more than any other group was adult women. Now this meant a lot to me because I've spent a lot of my life trying to appeal to adult women. That's always been something I thought was a good idea. so I really felt good about it. And people would ask me, well, why, you know, why did Yars revenge of all things appeal to adult women? And the only thing I really think of is you look at Pac-Man and you look at Yars revenge, they really don't have a lot in common, but there's one thing they profoundly have in common. What is it? It's eating, isn't it? Speaker 1 (16:41.492) Exactly. It's eating and yards revenge. must eat away the shield to enable the Zorlon cannon to win the game. In Pac-Man eating is the way you relate to the entire world. It's all you have is a mouth. And so it's I just thought it was very and so I figure that's it. So if you really want to appeal to women in video games, you have to do it bite by bite as they say. That's a very computer joke. Of course But it was interesting. And then I had a conversation with the marketing people and they said, Hey, you've been clamoring for a game for women. Here's a game for women. How are you going to market this to adult women? I think that's really cool. And the marketing guy said, we're not. And I said, why not? And he says, because it's a space action shooter. And I said, yeah. And he goes, well, women don't like space action shooters. And I said, but your own testing says they like this game. And he goes, no, we're not. No women don't like these games. So we're not going to do that. And it was like, oh my God, this is that, that conversation is a microcosm of what, one the, one of the real things that was difficult at Atari, which was the interdepartmental friction and consternation that would come about. When we would talk them about marketing or when they would talk to us about tech, it was like, just, never made any sense what we heard from them. And they kept demanding things from us that were absurd. And there was no appreciation for how much we were getting out of the machine. Like, Howard, like you were saying before, it's like the games. Most of the games up to that point were like the blue blob and you know, just straightforward falling stuff and very simple animations. Speaker 1 (18:36.854) And then when we started to really develop techniques like in ER's revenge and in some of the games that started to come out where it was much more generous, it was a lot of work and a lot of ingenuity to create that, to get, pull that out of the machine, a machine that nobody thought would do more than eight or nine games in the beginning. The designers of it figured it had like eight or nine different games in it. And we were getting to hundreds of games and There was a lot of animosity between engineering and marketing because we thought they were like surface level, simplistic, ridiculous, oafish kind of people. They thought we were a bunch of entitled, undisciplined, unruly, rambunctious, know, just kind of thing of the work. Just sort of like just crazy running around children who were being indulged. And except we kept putting games out that were selling a lot. But outside of that, we seemed really unreasonable. And they were driving a tremendous amount of sales through marketing and stuff like that. We couldn't figure out how they did it because when we would talk to them, it seemed like they were insane or just totally unaware of the product. And so that's another thing that I do talk about quite a bit in the book that a lot of people have. I've got a lot of feedback on this, that people I described the actual infighting and how to deal with the interdepartmental conflict between engineering and marketing. A lot of people have come to me, not just in games, but in software development in general, who say that the things I described there still ring true in their companies today. And it's true. And it's one of the reasons why I became a therapist, right? A lot of people think it was a very unusual move to go from being a programmer to being a therapist. And to me, it seemed like a very natural evolution, you know, because if you think about it, programmers and therapists were all systems analysts, right? It's just that I've moved on to a more sophisticated hardware in the human brain. And the other great thing about it is brains don't really change that much every four years. There's no Moore's law for psychology. It's like in computers, you keep having to relearn everything every few years. It's just kind of a pain. I figured, you know, people, individuals can change, but people don't really change over time. And I just thought that was an easier thing to deal with until I started doing it. Speaker 2 (20:56.13) Obviously Yars' Revenge sold millions of copies and your second game, which we have to talk about Raiders of the Lost Ark, I'm going to make a confession, Howard. I sucked at that game. When I got hold of a copy, I got an unboxed copy and it came without a manual. I didn't know. What am I doing? I couldn't make head nor tail of it. And I knew, I knew I had a good game on my hands. I just didn't know how to play it. I went online and found a guide to play it and it helped. It helped. But before I get to the game's complexity, obviously this was the first licensed movie adaptation, the first Indiana Jones game. Indie was a household name at that point. The movie had come out the year before, is that right? Or two years before? Was there a lot of pressure to get it right? Well, yeah, but what does get it right mean? That's the tricky thing. There was a lot of pressure. I felt a lot of pressure. So my first game was a big success. And now I get to do the first movie to game conversion. So there's a lot of pressure. mean, there's a lot of expectation on the part of people out in the world, but the real pressure was going on in my head because I thought Maybe I just got lucky with yards. Am I a one hit wonder? The insecurity starts to bubble up. Right. And it was a very lonely place to be in a lot of ways. It was an honor to be there and it was great to be selected. And, you know, Spielberg had to interview the programmers to pick someone to do Raiders. And that was one of the most amazing days of my life was the day I went to go interview with Spielberg to see if I was going to be the one to do Raiders of the Lost Ark. A story which is covered extensively in the book Once Upon Atari, I just like to say. Because I had to fly down to LA and go to Warner Brothers Studios to their lot to show up for the interview. And I'm 400 miles away. I actually had to take an airplane and the more I got up early, took an airplane to go down for a 930 AM interview. I got there. I show up and Speaker 1 (23:13.198) I walk in and the receptionist is there and I go, hello. I'm, and they just look at me and they go, hello, Mr. Warshaw. Your interview has been rescheduled to three 30 this afternoon. I flew here. You know, I have a flight back and, but I'm. I'm a make lemonade kind of guy. It's like, first I thought, what did your six hour delay? But I thought, you know, I am a huge movie and television fan. I'm here in the middle of Warner Brothers studios. And so first I just said, look, can you, can you fix my ticket? I need a later flight back. And she said, Oh, no problem. And she took my ticket and was going to fix that up. And I said, so I said, uh, is it okay if I just wander around the studio until three 30? She goes, Oh, sure. Go ahead. So I got to spend a whole day on escorted walk free rain going all over Warner Brothers studio. before meeting with Spielberg. mean, I jumped into sets. I stole things off of sets. I went everywhere. This was like an amazing opportunity for me. At the end of it, I get to see Spielberg and then I do show up and there's Steven Spielberg and we start chatting. We played some Yars revenge and he liked Yars and we were talking. It was going well. I thought we were establishing a nice report and then it occurred to me. You know, Steven, I have this theory about how you're actually an alien yourself, you know, would you like to hear it? And he's like, yeah. And so I laid out, had this whole theory about how, you know, the aliens aren't going to just show up in a spaceship. You know, they're, if they're smart enough to get here and observe us, they're going to send an advanced team to culturalize us, to get us ready. And in the, in the early eighties, it really felt like that's where we were. And one of the major reasons was close encounters of the third cut. So. I explained to him how I think, you know, they're going to have an advanced team and he's like the production arm of the team. And he makes these movies that show aliens in a positive light and his marketing team makes sure they're seen everywhere all over the planet to get everybody on earth ready to receive the aliens. And I said to him, so I said, first of all, I said, great idea, great team, and you're doing a great job. so I, so that's what I told him. And then we sort of wrapped up the interview and then I went back home and the next morning. Speaker 1 (25:37.25) He just called into Atari. just said, Howard's going to do the game. And I think calling him an alien is what got me to do the game. But now Steven Spielberg, my idol, who I now have to do a job for, who I have to do a work for, that's a derivative work of one of his definitive super hits. Holy crap. Yeah, but what a game. think, you know, when I look at Raiders for the 2600, it's not your standard kind of adventure game, just running from one side of the screen to the other, hammer the button a few times. There's a sophisticated kind of inventory system. There's puzzles. There's, you know, taking things from one place and to another. And unlike Adventure for the 2600, where you can only carry one item at a time, you can carry six. So you're juggling all your inventory and stuff. Wow. What a game. I hear it was a very deliberate choice not to make it a kind of action game. It was in it to me it was clear that it needed to be an adventure game and my goal I always have a goal with each game You know my goal with yours revenge was to establish myself and really break new ground and show people I can not only make a game I can make a splash I can really do something I wanted to have credibility and then with Raiders my goal was to make the biggest adventure game on the 26 anybody could imagine awesome And that doesn't mean just taking one screen and replicate it, you know, like 255 times, you know, with whatever, just to replicate that. To me, that's not making it big. That's making it long. But I want to have new, fresh gameplays, different things to do, different ways of approaching a game period. And also Adventure was a genre defining, real breakthrough kind of game. Adventure was a simple game, but it was brilliant. And it really Speaker 1 (27:38.67) It was a killer app, Because it showed people a whole different idea about gaming, how you could engage a game. And so if I'm going to stand on the shoulders of that and make a sequel adventure game, it has to go further. It has to go beyond because each game has to be a contribution. That's where I was coming from. So I want to do something that was the biggest adventure people could imagine. I used two controllers for one person. I made inventory control of actual part. That's gameplay. And I specifically, one of the most controversial choices in the game was that I fixed it so the controller that's normally the first controller that everybody goes is the default controller. made that the inventory control. couldn't move with that one. You had to use the other one. And it was a way of queuing people to say, look, there's going to be things about this game you're not used to. So you need to look, you need to find information. And this was also pre-internet. You know, so you were able to go online, find the manual, get that going. People couldn't do that back then. I pity the fool who had to play that game without the manual back in the eighties. But it was all, this was all specific, intentional stuff on in my head to do what I felt was the most breakthrough version of an adventure game I could think of. The one thing I'll say about Raiders is it does have the best animated legs on the 2600. Indie's legs are beautifully animated, but I think to modern audiences and for some 2600 games, the graphics are more symbolic perhaps than completely representative. I wonder if it was... I've often found myself thinking the gameplay in Raiders is so fantastic. Was there any demand to have it like an updated version for the later Ataris, the 7800, something like that? Was it a kind of one and done? Speaker 1 (29:44.438) No, it was pretty much a one and done. Most of the games on 26th of December were one and done. So, I never heard of anybody trying to do more with Raiders. Just like, you know, some people do ask for it, but at least around Atari, no one ever regretted they didn't do ET or wanted to do something else with ET. think that the mechanics of Raiders is so interesting, but with a graphically more capable system like the 7800, it could have been a game that absolutely knocks it out of the park for the system. Absolutely. would have been, I mean, you could do a much nicer version of Raiders. I could make it even bigger. Some of the stuff could be more representational and clearer. Also could have game hints in the game, which would have been a wonderful thing to do. Okay, we're going to move on to ET. It's often called, I think very unfairly called the worst game ever made. think that is. And a lot of people will say it's the worst game on the system. And again, I would disagree with that. I personally think there are many, many worst games for the 2600. I had quite a lot of fun with ET once I got used to it. And once I figured out how to avoid falling in the pits and stuff like that. But, Thank you. Speaker 3 (31:04.462) It's It's a remarkable achievement though because you programmed this one in five and a half weeks. Tell us a bit about it. Exactly five weeks, five weeks and a half day. Yeah, it was, I found out I was going to do it on July 27th and I delivered it late in the evening of August 31st and it was approved for manufacturing September 1st. and Spielberg approved it himself right here. Absolutely, I insisted on it. Speaker 2 (31:32.108) Yeah. Did he fall in the pits a lot? When he played it, he fell in a fair amount, but he was able to work out of it too. He really didn't have much of a problem getting out and going on with the game. It was actually pretty impressive. in the pits is part of the game. People are like, I fell in the pits. Well, that's like saying I was in a maze in Pac-Man. That's how the game's played. It's mechanics. The pits are an inherent part of the mechanics and have to be because that's where the replayability came in. To do a game in that short amount of time, what you need is a smaller game that you can replay, you know, like a Sudoku or a Tic Tac Toe in a very simple version. There are some games that aren't meant to last. They're meant to play and play again and play again and play again. The idea behind ET is that there are several, it's a series of treasure hunts. You know, it's a series of things where you have to locate something, put it together, and then do something with it that takes you to the next step. You have to assemble the phone pieces and you have to find them where they are, put them together, and then you have to find the place where you're going to call home. And when you find that, you execute the call home, then you have to go and find the landing spot. And when you find the landing spot, you have to organize it so that you're there alone without any of the humans so that they will come and pick you up. And so it's a sequence of those. Speaker 1 (32:51.694) And as long as you have enough places to hide things, you can randomly redistribute them. People can play it again. And if the basic treasure hunt is fun, people get immediate gratification for running through it again and again and again, which a number of people have. I agree with you that it's not the worst game on the 2600, but I have to tell you, I do prefer when people do identify it as the worst game on the 2600. And I'll tell you why. because, you know, Yars Revenge is frequently cited as one of the best games on the 2600. So as long as ET is the worst game on the 2600, have the greatest range of any game designer in history. Yeah. You're, you're bookending the 2,600 then aren't you this? love it. Yeah. Um, okay. Whilst, whilst we're on it then, if, we leave Yars' Revenge as the best out and we leave ET as the worst out, what do you think? I mean, the 2,600 had a huge library and I did want to talk about a bit about it because I think it's a great system for collectors, collectors on a bit of a budget because It's not an expensive system to collect for and with the recent release of the 2600 plus that has a HDMI port, you can go to town. What do you think is the best and worst game on the system other than your own? best game and there's a number of pretty good games on the system. you think Rob Fulop is a designer who I really respect on this system and he did the missile command version. think Demon Attack is an extraordinary good game. I really like that game. Speaker 2 (34:34.988) so fast, Demon Attack. It's... Yeah, that's a cracker. Beautiful game. It's really well done visually. He does a number of things also innovate. I have an eye for innovation. I respect that. I want to create it and I want to do something breakthrough. I want to break new ground with each game and I respect games that do that. I think Kaboom is a great game. Also, it's a very simple game, but it's compelling. You run back and forth. It's it's one of those games that sucks you in and you it's a game you sit down to play for five minutes and then suddenly it's an hour and a half later. What happened? You know, it's a game you can lose yourself in. And I like that in terms of horrible games. I can't use ET. Let you use it. You've mentioned two games there, Demon Attack, which was published by Imagic and Kaboom, which was Activision. Now I want to take a little moment on Imagic games because they didn't have a huge library, they put out my vying with Yars' revenge. My favorite game on the system was Dragonfire. I don't know if you ever played that one. It's an unbelievably fast paced little kind of, I don't know, I would say firefly. Speaker 2 (35:46.87) Twitch game basically. then Activision, obviously they did Kaboom, but they did, I'm wondering was there really any animosity between you guys in Atari and Activision who kind of were the new kids on the block and came along and just made some absolutely amazing games for the system. Well, okay. So the formation of Activision and a magic and the whole history of all of that stuff is covered at length in my book, Once Upon Atari, how I made history by killing an industry. And it is an interesting story because they were all started out of Atari, right? Activision was formed by what were the top four programmers at the time at Atari. And then a few years later, a magic was formed by three more. successful programmers at Atari and some programmers from the Magnivis, the Intellivision system rather. so Atari had a history of losing key employees because they really didn't want to pay anybody. Initially, we would have paid to do what we were doing, but after a while it became so clear that so much money was going on and so little was filtering down to the people. who were actually making the games that people left the company to get the opportunity to actually get what they felt was more reasonable pay. And then Atari ultimately ended up having to pay also because Todd Fry, the guy who did 2600 Pac-Man and the Sword Quest series and me, we were going to leave to form another company. And Todd told Atari about it. And then suddenly we got a big bonus plan. that worked well. And so we ended up staying there. Otherwise, Raiders and ET might not have happened the way they did. yeah, and one thing about ET, there's one thing, couple of great things about ET is the ironies, because there's a lot of irony around the ET project, Atari in general. But the two great ironies of ET, one is that a game that was all about pits wound up in a pit. If you saw the Atari game over, that to me is one of the great ironies of ET. Speaker 1 (37:58.06) The other one is that ET, another unusual thing about ET, mean, ET also, even though I only had five weeks, I still wanted to break new ground with the game. So ET is the first game that has like location specific power ups, right? It's you don't have just one power throughout the game where you go, your powers shift depending on where you are. So you have different abilities and that factors into the strategy. And also it's a three dimensional world. I think it's the first. 2600 game that actually is played in a three dimensional world that holds up that you follow it But what it's a totally nonviolent game, right? No one gets killed or maimed or anything like that ET is a totally nonviolent game and so one of the great ironies is that a Nonviolent game is responsible for killing the industry for those years So I just I love irony. So I just thought it was interesting I think it was established like at first ET sold really well. So when did you become aware of the backlash? How did you become aware? And then at the time, how did you take it? Really good question. Really good question. Yeah, because this was pre internet and people have a hard time conceiving of pre internet now. So before the internet, what it meant was when you finished the game, it was going to be several months before anybody got the game. Right? So I finished the game for September 1st. It didn't hit shelves until mid November. So nobody saw it before then except for our internal testing. And then It was also, it was a huge Christmas present, which meant a lot of people bought it as a Christmas present. So a lot of people bought the game, but no one had played it yet. They didn't open it until Christmas. It wasn't until like right after Christmas and into January that the massive feedback started to come back. Now the other thing is, is because there's no internet, you don't drop a game. You put it out on shelves in stores and people buy it and take it home and play it. And they don't have an online. Speaker 1 (39:55.692) forum to go and give the feedback, right? So you don't get this massive wave, but there was a lot of word of mouth that there were problems with the game that people didn't like it. That started to come back about February. It was around February when I started to get feedback that there were some issues with the game. There were some returns coming back. People weren't that happy with it. And so you have to remember. So since the previous September, So this is like five and a half or six months after I'm done with the game. I'm working on other games. I'm trying to develop new stuff. My head has been so far away from that that when this comes up, like, it's kind of, it feels to me like old news, although it's fresh in terms of the market and what's going on. And the reviews would start to come out, but those were slow because the gaming magazines only came out like once a month. Right. So all the information, all the feedback was delayed. And because there's no internet, there's no drop and there's no update. So whatever you put out on the 2600 back in then, whatever you put out, that was it. No one's going to go remanufacture the car to fix a bug or something like that. So the pressure wasn't just to do a good game. The pressure was to finish it and it's a drop dead date and you cannot do anything else with it. So it was, it was also a little tougher than there was a lot of pressure. There was a lot of pressure, especially when the money started to increase and we started doing bigger and bigger licenses. I'll tell you one of the things that was Atari was an amazing place to work. mean, amazing with really cool people doing really interesting stuff, but there was a lot of pressure and not everyone could handle it because there were, there were more nervous breakdowns in that department at Atari than any place I've ever worked in Silicon Valley over like 30 years. People, you occasionally you would go in and you would literally find someone catatonic in their office. just sort of staring blankly at something. We actually had people carted away. We actually had people, people had to come and help them out and take them away to facilities where they could heal. But it was, was, it was fun. It was wild. It was exciting, but it was also brutal. And it took a toll on all of us. Speaker 2 (42:11.276) Another thing with, I've been watching the documentary Atari Game Over just recently for I think the third time I've seen it now. But obviously knowing we were going to do this interview, I thought I'd better swat up again. Obviously it was a complete urban legend for ages that Atari had buried all of these consoles and controllers and copies of the game in the desert. And then the the documentary for those that don't know it, it looks at how these were excavated and stuff and you played quite a big role in this. What was that like for you as an experience watching your game get dug up out of the ground? It was intense. It was intense. If you see the movie, you will see the emotional reaction that I had. Honestly, I've seen the movie quite a few times, as you might well imagine. And I'll tell you, every time I see that part of the movie, I still get choked up. And some people at the time thought, I'm getting upset because my games were in the day and I never thought they were. But the reasons I didn't think they were there were practical reasons, not emotional reasons. When the game came up, And there it was. I had a deeply emotional reaction, but it wasn't about the idea that my game had been buried. That wasn't it at all. What it was was I'm there in the middle of a crowd. This is in the middle of a dump. This is a city dump in the middle of the desert in Alamogordo, New Mexico. I don't know how often you go to dumps. I've gone to dumps occasionally. I've never seen a line of people waiting to get into a garbage dump. But that day when we went there, there were over 400 people who were all lined up waiting and eventually came into the dump as the day progressed. And there was this huge throng, this huge crowd, there were local officials and there were food trucks, you know, and there were all kinds of people there, but there was the film people, there were the construction people who were digging everything up. But most of these people were fans. They were classic gaming fans. Speaker 1 (44:17.174) And so when the game actually came up, was so exciting. was so exciting. Everybody was cheering and yelling and people were really happy. And it was just, and what I realized in that moment, it took me back to, like I said before, the way I came to games was different from the way a lot of the people who made games came to games. To me, it was about films. It was about a broadcast media. I always felt games were a broadcast media. And you know, when you think of producing media like, you know, a podcast. It's like, what's your goal with a podcast? What's your goal with a piece of media? To me, my goals with a piece of media is threefold. I want to entertain, I want to inform, and I would like to generate social discourse. And if I can do all three of those with a piece of media, I feel that's a tremendous success. And in that moment, with all these people cheering and people from news outlets all over the country and some cases around the world were there to cover this event. And here it is, it's happened and they found it and wah-ha. So the urban legend is kinda true. Wasn't perfectly true. But to see that crowd going and what I realized in that moment was this thing which is just K of computer code, of assembly language code that I had written. 30 years earlier was still generating such interest and such focus and such excitement and to have been at the center of that and to be the cause of that. How many people who put out a piece of media get to see it still being celebrated 30 years later? Not many. It's a rare opportunity and it was overwhelming for me. but it was joy, it wasn't disappointment, was joy I was feeling. To have created this fun and this excitement and this positivity, it just meant so much to me, it literally brought tears to my eyes and it made it hard to speak. Speaker 2 (46:21.346) That's brilliant. I mean, for anyone that's seen the documentary, the novelist Ernest Cline borrows George R.R. Martin's DeLorean and drives it 400 miles to come. I mean, it's it's quirky stuff like that, but it is. Actually, people were at borrowed. was it was Ernie Klein's DeLorean that Martin had borrowed for a screening and Ernie had gone and picked it up and he was driving at home but stopped at the Alamogordo on away. Yeah, I think, yeah, you could see that how much it meant to people that they came and spent the day there, even though there was no guarantee they'd find anything. And yeah, it feels like the movie itself is 10 years old now or 11 years old. But it's such a celebration of that era of gaming, which has largely been sort of, it's not been forgotten, but it's been superseded by the sort of Nintendo era and stuff. but I think it's such a such an important part of gaming history. And I'm just thrilled to have you here. I've got one more question before we move on to our questions that have come in throughout the thing. I think there's still quite a vibrant homebrew community for the VCS, which I think is absolutely fascinating. And again, as I said, with the advent of the 2600 plus, you know, it's so much more accessible to people. But are there any new games for the 2600 that you particularly like? There's a group of people that's headed by David Crane of Pitfall fame. So I think it's an excellent game. And the Kitchen Brothers, Daniel and Gary Kitchen. And they together put out, they're doing new games on the 2600. They're doing some really excellent stuff. They have new tech that they can use to host the games. And they're still stretching the possibilities and the capabilities of the 2600, which is... Speaker 1 (48:17.706) Amazing to me that that's still happening the idea that someone wants to go and torture themselves in this way to create games on the 2600 because After the 2600 everybody had bitmaps. They had things they had simplistic versions and it got more and more sophisticated But the 2600 was the last game that didn't have a bitmap In the 2600, when you're programming the 2600, you are literally driving the electron beam as it would go across the screen and make modifications at the millisecond, microsecond accurate level, to be precise, and to make some of the things happen that we were able to make happen on the screen. It was excruciating kind of programming to do, but it's a really fun puzzle to solve. And I think the idea that it's so much of a puzzle and so much of a challenge. that that's the thing that's keeping this alive. That programming the 2600 was fundamentally different than programming any other kind of machine and it was a different kind of mental exercise and challenge and I think people are still enjoying it. The reason people are still doing it is because I think they're enjoying that challenge of what's involved to do it and it's a fun puzzle. Yeah, I read an excellent book several years ago called racing the beam, explaining the difficulties of, of, of programming the system. I, I just wanted to mention, I don't suppose you played Ed Fries is, halo 2600. So Ed Fries worked for Microsoft and worked, think on the original halo and he ported halo. I really recommend checking it out. It's, pretty old now, but, Wait, no. Speaker 2 (49:58.414) think it was about 2010 he brought it out. is a remarkable achievement to be able to play Halo on the 2600 or a version of Halo. But I'm going to hand over to Cal now for some of the questions that have come in online. Cal. Yeah, just two remaining questions. As you can see on the screen, do you enjoy games like River Raid and Pitfall? Absolutely. River Raid was done by Carol Shaw, who was the first VCS, female VCS programmer. And then she left Atari and then later joined Activision where she did River Raid, which I think is a superior game. Absolutely. And Pitfall, you know, there was a contest between Pitfall and Raiders to see which game was going to go into the Smithsonian as representing an adventure. And Pitfall won. Hats off to David Crane. And there's one more question. Indy's legs were better animated than Pitfall Harry. just want to say that. Indy's legs are better than Pitfall Harry's legs. My graphics designer, Jerome Demuret, would be very grateful to hear that. And another question there, did you ever meet Steve Jobs and Wozniak when you were at Atari? Speaker 1 (51:13.056) No, I didn't. met was in an airport in San Jose a couple of years later, but they they had left Atari by the time I got there. They did work next door, though, and we stole their sign. The Apple building was right next to the Atari Engineering building and we stole their sign once. And that was they were not that happy about that. So we're coming up to the end. So we didn't actually touch on a few things, Howard, but that's the nature of these things. So we're going into a quick fire round. If you're ready for some kind of not at all serious quick fire questions, Howard, you can give an answer if you want. How exciting. Right, go for it. Right. Well, this one's more, this is definitely for Howard, this one. What was the best smell you remember from the Atari office? The best smell I remember from the Atari office was the smell of success when you got a good report back on your gang's noise. Alright, so here's another. In a therapy session, what's worse, silence or the buzzing sound of Yars' revenge shield? Silence is more ominous. If I ever heard a client in meaningless song of yore's revenge, I would be very concerned. Speaker 2 (52:24.558) I would say silence. Silence is okay. And one of the things we learn when we're training as therapists is just to hold that silence. it's, think it's a real skill. I personally do prefer the buzzing sound of the Yars revenge though. Right. It's more of a throbbing and electronic throbbing, isn't it? It is. It was made to reflect the sci-fi lab experience of all the 50s sci-fi dramas with the arcing things. That's the origin of it. That's the thinking behind it. So it's very relieving to hear you say it. The throbbing is absolutely there. Yeah. So next one, what would you consider your spirit animal? Yar, the Radar or ET? That's a good one. I would say it's somewhere between the R and ET. Although if you put an A in the middle of ET, you get eat, which is really my spirit animal. Next one up, did you wear a fedora while you were coding Redis for the Lost Ark? Speaker 1 (53:22.038) Not only did I wear a fedora, I had a 10-foot bullwhip. I got very good at cracking it. One of the things I used to do is when marketing people or suits would be visiting engineering, I would sneak up behind them and I'd crack the whip and they would jump out of their skin. That was good for relieving some tension during a tense day. This one's for both of you. What's a piece of common technical jargon you wish could be replaced immediately by a psychological term? I've got that one. Alright. The piece of technical jargon would be PEDKAC. P-E-D-K-A-C. And what it stands for is problem exists between keyboard and chair. the way I would replace that is with personal responsibility, taking responsibility. Speaker 2 (54:17.966) I gotta confess, I am technologically inept. I'm quite comfortable working with people, but when it comes to technologies, I had a TV when I was an undergrad student, many moons ago. wouldn't, for no one in the house, it would fire up. You you put it on, it was one of these old cathode ray tellies, you know, big box, and it wouldn't fire up. But we discovered that if I took my left trainer off, It had to be a specific trainer that I had. It was only my trainer, my left trainer. I could bang the television with the trainer and it would switch on, but it would work for no one else in the house, no one else's shoes, just me and my left trainer. I'm sure there's a therapeutic application there, but it's probably not ethical. Oh, wait a minute. I have a little surprise. It's the elephant in the room. What's he saying? He's saying, don't forget to check out Once Upon a Time in How I Meet a Mystery by Howard Scott Warfarin. So I hope if you've enjoyed the book, pick out the book. I think if you like this talk, you will very much enjoy the book. I'm going to have to check it out. absolutely love that picture of you on the cover. Fantastic. Was that whilst you were programming ET or when you'd finished programming? This was this is day this is day four of the project. This is my birthday. I'm in my office. And if you look up here, that's you can see one of the screens for me. Speaker 2 (55:52.782) Okay. Right. Two more of the quick fires left. Where are we? When you walk into a room, do you think of yourself as a programmer who talks to people or a therapist who knows assembly code? very much a therapist who knows assembly code much more so. I always felt out of place as a programmer because I was more people focused. And the last one is what's the ultimate design constraint? Four kilobytes of ROM or a 50 minute therapy hour. 4K of ROM is a much tougher restraint than 50 minutes for a therapy hour. You can do a lot in 50 minutes with a therapy hour. Perhaps the ultimate constraint is five weeks and half a day. Speaker 1 (56:36.162) That is the ultimate kill string. All right, thank you so much, Howard. And, do you have a final thought there? No, I just want to say to Howard, it's been such an absolute pleasure talking to him. As I've said to anyone that would listen in the last week that when I agreed to do this interview, this is talking to a game design legend. So, Howard, thank you so much for being with us this evening. And it's been a real pleasure. This was my pleasure, ISU. Herward and Cal, thank you so much for having me. This was really wonderful. I really enjoyed it. No problem. And if people want to reach out to you, if you've got any other further questions or they want to hear any more, well, there's the book obviously. And if there's any other ways they can get a hold of you. I'm very easy to find online. can find me at hswarshow.com or you can go to onceuponatari.com and contact me through either of those. And you can find Once Upon Atari all over Amazon or anywhere else, the audio book or anything else. Please enjoy it and enable me to write another book. Speaker 2 (57:45.718) And the chat room just reminded us a question that I have left out that we ask of all our guests. Would you consider a visit to the Hebrides? Absolutely, I would consider it. I'd even do it. All right, that's good. Well, watch the space. Something might happen sometime in the future. So thank you, Howard. It's been an absolute pleasure. Thanks, Edward, for you. We don't have you on often these days, but as always, good to see you. And thanks to the chat room for the great questions. And we'll see everyone very soon. Good night.

1 thought on “From Atari to Therapy: Howard Scott Warshaw’s Journey”